Swimming can help people with autism spectrum disorder

Erika Gleeson of Autism Swim looks at how swimming lessons can help mitigate the leading cause of death among children with autism spectrum disorder - drowning - which accounts for an astounding 90 per cent of deaths.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a lifelong neurodevelopment disorder, which is categorised by the following (excerpted from DSM5 manual):

• Persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction across multiple context;

• Restricted, repetitive patterns of behaviour, interests, or activities;

• Symptoms must be present in the early developmental period;

• Symptoms cause clinically significant impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of current functioning;

• These disturbances are not better explained by intellectual disability or global developmental delay.

ASD affects almost 230,000 people in Australia; 64,400 people were estimated to have the condition in 2009.

Drowning is the leading cause of death among children with ASD (University of the Sciences in Philadelphia, 2014).

According to the National Autism Association, accidental drowning accounted for approximately 90 per cent of total US deaths reported in children with ASD ages 14 and younger in 2009 to 2011. Statistics in Australia cannot be found; however it is hypothesised that the percentages would be comparable.

The question is, why are the statistics so high?

Reasons for high drowning rate

Wandering

Wandering is the tendency for an individual to try to leave the safety of a responsible person’s care or a safe area, which has the potential to result in harm or injury. It is often referred to as absconding, elopement or fleeing.

It is not uncommon for individuals with ASD to become overstimulated by crowds, noises and a range of other stimuli, hence escaping this by retreating to another environment. Many individuals with ASD gravitate towards bodies of water because they associate water with alleviating many of their sensory needs. Research indicates that nearly 50 per cent of children with ASD attempt to escape from a safe environment, which is a rate nearly four times higher than children without autism. Fifty-eight per cent of parents of ASD children report wandering/elopement as the most stressful of ASD behaviours (National Autism Association).

In addition to drowning, wandering brings with it other high risk factors, including but not limited to exposure to the elements; dehydration; falls; hypothermia; traffic injuries; encounters with strangers; and encounters with law enforcement.

Difficulties with generalisation

Generalisation refers to ability to transfer skills and information learned in one setting to other settings, people and activities. Sixty-eight per cent of the individuals with ASD who represent the 90 per cent figure above, died in a nearby pond, lake, creek or river. So although many individuals with ASD may have had swimming lessons and developed swimming skills in pools in the past, they may experience difficulties in generalising this skill across different environments (lakes for instance).

Lack of specialised services

Many swimming teachers may have undertaken additional training in “special needs”. However, until recently, there has been a severe lack of specialised training specific to ASD and swimming. There is a need for teachers to understand the ways in which individuals with ASD process information and acquire new skill sets, so the sessions can be individualised and tailored to the strengths of the individual. There is also a need to incorporate components of water safety into the lessons.

Difficulties with perceiving danger

The risk of drowning increases with the individual’s ASD severity. Many individuals with ASD have difficulties with anticipating danger and judging risk, which is exacerbated if they also have an intellectual disability.

Lack of awareness

The data also showed that only 50 per cent of parents of children with ASD have received advice about wandering prevention from a professional. Sadly, many in our community are unaware that wandering is even an issue or that drowning is such a high risk factor for individuals with ASD.

What can be done?

Talk

Interest in this issue and in articles such as this is a beginning. As with most things, awareness and education is key. From 2009 to 2011, 23 per cent of children who died following a wandering incident were in the care of someone other than a parent. Talk with those around you and educate them on the risks.

Wandering/drowning is most likely to occur under the following settings:

• During warming months

• Visits to non-home settings, such as a friend’s house or when on holidays

• During family gatherings

• During times of stress or escalation, which may cause the individual to flee or wander

Take extra precautions and plan accordingly. Family gatherings or other events may give a false impression of high supervision, which is often not the case.

Government initiatives

This is a worldwide concern. However some countries are leading the way in prevention initiates better than others. The USA for instance, has developed a Big Red Safety Box. This is inclusive of a range of preventative and reactive resources in relation to wandering including emergency plan templates, individual identification aids, checklists and signage; and it’s free!

The more that awareness is raised, the higher the likelihood governments will respond.

Enrol children with ASD in specialised swimming lessons

Allow individuals with ASD the best opportunity possible to learn water safety and acquire swimming skill sets. Enrol them in specialised swimming lessons being run by Autism Swim approved instructors.

Positive behaviour support

If your child or a child you know has a propensity to wander, consider positive behaviour support to ameliorate this. Behaviour specialists will undertake an assessment of the behaviour and design associated strategies and programs. An occupational therapist may also be able to assist

Case Study

Andrew is a 14-year-old young man with autism spectrum disorder. He is non-verbal.

Andrew’s history prior to being engaged in specialised lessons is such that he had limited exposure to swimming due to his some sensory challenges in relation to his face being in water.

He could effectively dog-paddle for a maximum of five metres. There was no functional swim stroke and he had very limited confidence.

Andrew started specialised swimming support through his Autism Swim approved instructor, Georgia. The initial goals were to teach Andrew to tolerate his face being in water and to get into and out of the pool safely (including holding onto the side of the pool until otherwise instructed). Through a mix of program designs, Andrew mastered the safe entry and exit out of the pool and holding onto the side of the pool within five weeks.

Through an applied behaviour analysis-based shaping program, Andrew achieved his goal of face-in-the-water within eight weeks. Once this was achieved, new goals were set. Andrew was undertaking two 30-minute sessions each week and within six months he was able to master freestyle kicking, freestyle arms and floating.

He uses a kickboard independently and shows confidence and aptness in the water. Andrew will now be transitioning to attend one of his classes with another student who is of similar skill-sets, to allow a social outlet for him.

Contact: www.autismswim.com.au

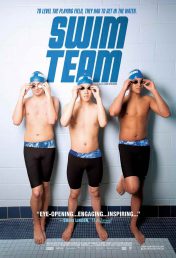

Swim Team

Click here to see a trailer for the new movie Swim Team, about an team of swimmers with ASD.

Click here to see a trailer for the new movie Swim Team, about an team of swimmers with ASD.